Superficially, Walmart Inc. and Costco Wholesale are very similar. Both are large, international, for-profit corporations whose primary activity centers around selling discounted goods to the public from enormous ”big box” stores that resemble warehouses.

But how each company achieves success shows a radical difference in business philosophy. That difference doesn't just have a huge effect on the lives of the retailers' customers and employees, it can mean delivering a boost–or absolute destruction–to whole regions surrounding these massive stores.

In short, Costco can act as an engine of revival for localities where its stores are established, providing more economic activity without eliminating local retailers. Meanwhile, Walmart holds out the prospect of low prices and hundreds of jobs while turning downtowns into deserts and leaving everyone wishing they had never come to town.

Here's why.

Doing business

The corporate statements of both companies make it clear that they are focused on a very similar goal: Providing a good return on investment to their stockholders.

And they do.

In 2024, Walmart provided $6.08 earnings per share—a jump of over 10% from the previous year. Costco blew past market estimates, reporting $16.60 earnings per share in 2024. Investors in either company have done very well over just about any extended period in their histories. Walmart shares are up over nine times their value in 2005. Costco's share price has soared from $41 to $860 over the same period.

Few investors are going to complain about those kinds of returns. Both companies also held their values well during the market crashes in 2008.

Walmart is the older and much larger company. It was founded in 1962 and has a total of 10,700 stores. Of these, around 3,600 are "supercenters" and 602 are "Sam's Club" stores. The number of new locations has slowed in the last two years, with around 30 new locations per year expected between 2025 and 2029.

Costco spun out of an earlier company, Price Club, in 1983. There are currently 914 Costco Warehouses, and the company expects to add 30-35 new locations in 2026. (The "Sam's Club" stores operated by Walmart are also modeled after the original Price Club stores.)

Costco is now operating in 14 countries, compared to 19 for Walmart.

The people strategy

Costco depends on long-term employees who are well compensated for their loyalty. Meanwhile, Walmart encourages “churn,” sifting employees for the handful it will advance.

An estimated 350 to 500 people are employed at the average Costco warehouse. That's similar to the average number of 300 employees for a Walmart Supercenter.

Post-pandemic, most basic Walmart employees (clerks, cashiers, stocking assistants, etc.) earn an hourly wage of $14 to $19 per hour. Raises are generally obtained, not through experience, but by rising to a position of "coach" or manager.

Costco offers the same class of starting workers a minimum of $21 per hour and provides regular raises, with an average pay of around $31 per hour. Last March, Costco signed an agreement with workers that promises overall pay increases in both 2026 and 2027.

Workers at Costco also enjoy more benefits, with full-time employees gaining access to those benefits immediately and part-time employees generally eligible after 90 days. Most Walmart workers are not eligible for many benefits until they have completed their first year, and part-time workers are only eligible if they average over 30 hours/week for a two-month period, making it very easy to manipulate schedules so that benefits are always just off the table.

Walmart's low level of pay and the difficulty of obtaining benefits are the primary reasons the company is among the largest employers of workers who receive Medicaid and SNAP. It tops the list in most states for the percentage of workers who need some form of government assistance to survive. Other retailers, incuding Amazon and Home Depot, also appear in the lists of companies with high percentages of workers receiving SNAP or Medicare. Costco does not appear among the top 25 companies in any of the states studied.

When Walmart moves into an area, it has a well-measured effect on the local community.

One of Walmart’s most detrimental effects is lower wages in the local economies it enters.

“Walmart may say they help people ‘live better,’” said David West, the now-former executive director of Puget Sound Sage and current labor and employment consultant at ChangeWorksNW, in the press release. “But this study shows that communities will be much worse off with lower wages and less money in the community after a Walmart opens.”

This decline in wages and draining of the local economic pool is known as the "Walmart effect."

There is also a "Costco effect."

A growing body of research shows that new Costco locations can raise wages and strengthen local economies. The effect is so consistent that analysts now call it the Costco Effect.

Unlike the Walmart Effect, which is linked to more business closures and lower pay, Costco tends to lift surrounding wages. The reason is simple. Costco pays even its entry level workers well, so nearby employers raise pay to compete.

It might seem that this would lead to businesses closing in the vicinity of a Costco, but the opposite is true. More on that later.

Walmart's low basic pay and hard-to-get benefits are only half the story. Because it's not as if Walmart isn't spending money on salaries—they are. It's just distributed very differently.

A store manager at even the most successful Costco warehouse can expect to make around $150,000 per year. The company also has relatively few regional or corporate management positions, and advancing to those positions represents a modest increase in pay. However, executives also get significant stock options. With Costco's rising stock price, these can far exceed the value of their salaries. That's how CEO Ron Vachris, whose official salary is $1.18 million, actually has a pay package worth over $13 million.

Walmart is shockingly different. The manager of a single Walmart supercenter or Sam's Club can expect compensation upwards of $500,000. Additionally, the store likely has two or more assistant managers, each of whom receives a pay package equivalent to that of a Costco store manager. So Walmart isn't actually paying out less in overall salary than Costco; it's just choosing to distribute that salary in a very different way.

There are also numerous regional "Market Managers" within the Walmart organization, who pull down around $600,000 to $700,000. And that's before getting onto the rising escalator of corporate execs. Considering this pay distribution, it's somewhat surprising that CEO Doug McMillon makes only around $27 million per year, including both stock and salary. It seems the largest retailer in the world doesn't reward its CEO like even a mid-sized tech firm.

The result within each organization is predictable. Costco compensates its general workers so well that they know they'd never match its overall package without making a jump into another industry, likely one that requires a college degree and experience. The result is fierce employee loyalty that keeps turnover below 6% in a sector where companies like Walmart see rates as high as 60%. Single Walmart stores have reportedly lost more than 75% of employees in a single year.

One reason for this isn't just pay, but the work levels—something that will become more obvious when looking at how the stores themselves are structured.

For Walmart employees to survive, they have to climb. The company has little incentive to provide them with extensive training or to invest in them as individuals unless they can fight their way off the bottom rungs of the company's ladder. It's a fiercely competitive system that fosters high levels of employee churn as new workers try to grab the gold ring before bad working conditions and low salary squeeze them out.

For Costco employees to survive, they have to stick with the organization and learn more about their jobs. Despite the company's rapid growth, over half of all employees worldwide have been with Costco for over five years. Not only does this allow Costco to save money on basic training for new employees, it can also spend some of those savings on much more extensive employee development programs. In return, the company has reportedly earned $100 million from ideas collected from an actively encouraged employee idea program.

Overall, Costco provides a good salary to many people at each store. Walmart provides a huge salary to a very few people at each store and even more for those who escape to regional or corporate positions.

Making a house vs. making a home

Walmart uses predatory pricing schemes and economies of scale to force local retailers into ruin. Costco bouys up local retailers by acting as a destination and a source for materials.

Walmart's overall strategy isn't hard to define. They are ruthless with suppliers, demanding extremely low prices in return for shelf space in their thousands of stores. They are famous for their logistics, using their extensive transportation and storage network to distribute goods to their stores in a way that smaller competitors simply can't match.

And they're well known for undercutting every local retailer until they have absolute command of a regional market. This is especially true in groceries, where Walmart often prices goods 10-20% below local chains and frequently drops prices on a few key, highly visible items. Predatory pricing, where the company sells some "loss leader" items at below cost to draw customers into the store, is a key Walmart strategy. Walmart has been known to raise prices in an area after local retailers have closed, leaving consumers with fewer choices while maintaining an effective regional monopoly on many items.

The range of items carried at Walmart is continuously growing. The average supercenter contains between 120,000 and 150,000 different items at any one time. This broad range of products is designed to make consumers think of Walmart as their first, and only, shopping destination for more or less everything in their lives.

By eliminating local competition, Walmart obtains what is known as a "monopsony," allowing it to pay workers less because there is no effective competition for their labor.

This helps explain why Walmart has consistently paid lower wages than its competitors, such as Target and Costco, as well as regional grocers such as Safeway. “So much about Walmart contradicts the perfectly competitive market model we teach in Econ 101,” Wiltshire told me. “It’s hard to think of a clearer example of an employer using its power over workers to suppress wages.”

In fact, when Walmart arrives in an area, it can depress wages even at other retailers as both businesses and workers struggle with the suppressive effect of Walmart's stranglehold.

Practically every aspect of Walmart's strategy stands in stark contrast to that of Costco. Rather than signaling an end to local business and a hollowing out of the regional economy, a new Costco often brings with it a business boom that "raises all boats."

In part, this comes from the relative rarity of Costco stores when compared to Walmart's overwhelming presence. When a new warehouse opened in central Maine, 1.8 million shoppers drove an average of 40 minutes to visit the store in its first year of operation. Those shoppers reported using those trips to visit over 1,000 other local retailers. Visiting Costco remains an "event" for many shoppers, rather than just another trip to the store.

Bolstering that aspect is that it's genuinely hard to buy everything you need at Costco. While the stores have famously stocked everything from coffins to a 72-pound wheel of cheese, much of the contents at any given site are always in flux. Visitors can count on being able to pick up the famous rotisserie chicken and a series of staples in the company's signature Kirkland brand, but anything else in the store is prone to being absent on the next visit.

The average Costco Warehouse has only about 4,000 distinct items at a time, and many of those items are either rare purchases, like TVs, or bulk items that are difficult for the average household to use effectively. While it is possible to do all your weekly shopping at Costco, it's not the way that most customers use the stores.

There's no doubt that Costco can cut into the sales at some local stores, particularly those selling groceries and electronics. However, rather than replace the local grocery, clothing store, or garden center, Costco acts more often to supplement those businesses by providing items that may not be stocked by local chains.

One of the biggest reasons that Costco has such a relatively tiny number of items at its big stores is that many of its standard, reliable on-hand items tend to be large. Three-liter bottles of olive oil. Fifty-pound bags of specialty rice. Seven-pound tubs of Nutella. Consumers who are prepping for the day when the world comes crashing down may keep their basements filled with such items (along with an ammo rack), but many families or individuals have difficulty effectively using many of the items Costco keeps on hand.

Costco is fine with that. You may not buy those big bags of rice, but local restaurants do. And food trucks. And school systems. And retirement homes. And anyone else who has a copy of the recipe book "Food for 50" on their shelves.

Providing bulk items to local retailers that they can reuse and resell in the community is part of Costco's strategy. Sometimes that means things that are used as components. Sometimes that means simply providing customers with a more reasonable portion of items Costco sells only in Brobdingnagian sizes.

In an effort to integrate their locations into neighborhoods, Costco opened its first mixed-use location last year with 800 apartments (including 184 low-income apartments) built over a store in South Los Angeles.

This isn't to say that Costco can't have a bad effect on some local retailers. They certainly can. And it doesn't mean that localities are doing the right thing when they give Costco decades-long tax abatements to lure a store into their area. Because that's a suicidally foolish idea.

But the effect of increased visitors combined with a rising wage base and resources that are often helpful to local retailers is why Costco's coming to town does not generate the footsteps-of-doom feeling that many local businesses experience on learning of Walmart's approach.

Costco's relationship with its suppliers is also vastly different than that of Walmart's. While the company seeks to get low prices and can drop suppliers unable to provide consistent quantities or quality, it doesn't have to bludgeon manufacturers into moving their operations to China or cutting worker pay like Walmart.

That's because most of Costco's profit comes from selling just one item: Memberships.

Last year's average merchandise markup, or gross margin percentage, was around 11% at Costco — far less than the 25% to 50% commonly estimated for businesses selling similar products. … Meanwhile, membership fees are about as close to pure profit as a company can get, and Costco raked in over $5.3 billion in fees from 68.3 million households and 12.7 million businesses.

Rather than breaking kneecaps at a supplier to gain another percentage of profit, Costco can afford to take the hit on their end, because keeping up the rate of membership renewals is much more important to them than the price of any product in the store. That's why you can buy a hot dog and Jurrasic-size chicken for peanuts … so long as you have that card.

That cushion helps Costco maintain long-term stable connections with manufacturers and suppliers. This ensures that customers find their staple products at reasonable cost and get the occassional big ticket item at medium ticket prices. Which keeps Costco's renewal rate on memberships humming along at over 90%.

All of this turns Costco into a support base for the local economy, and Walmart into a money scoop that routes cash away from sites unfortunate enough to be graced by their big blue presence.

We leave something of ourselves behind

Walmart opens more stores, but it also closes more stores. When it's gone, it can leave behind a devastated local economy. Costco is careful about selecting a new location, then becomes a part of its community.

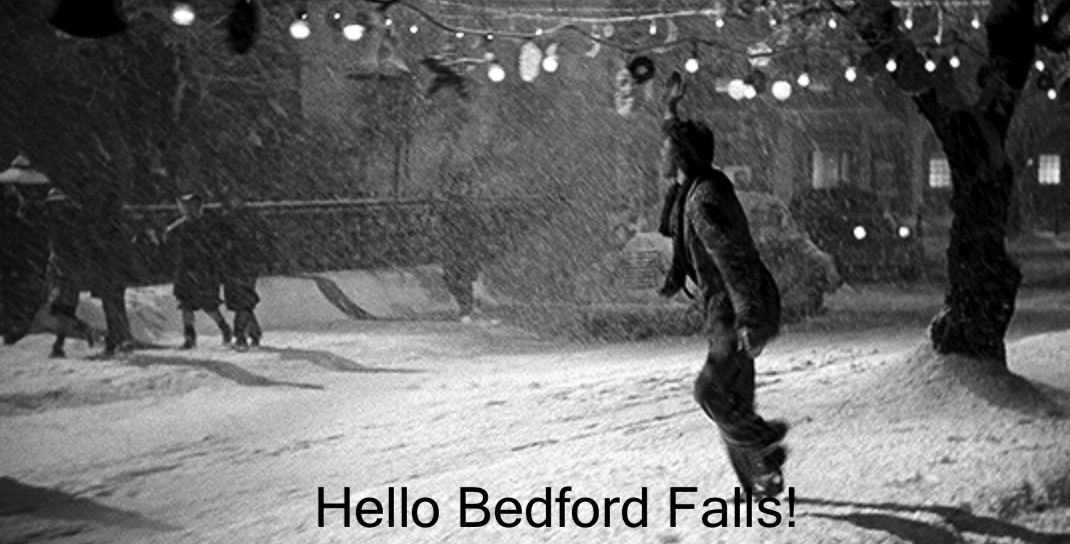

Walmart is fully aware that its practices can hollow out an economic region and leave scorched earth in its wake. In the last two decades, even as it continued to expand, Walmart has closed hundreds of locations. In an average year, it closes 15-25 lower-performing stores.

That's not locations where Walmart is upgrading an existing "neighborhood store" into a supercenter, or updating an older site. There are also no signs of any economic problem for the giant corporation as a whole. These are just places where Walmart was, and now isn't. If you have the impression that you've seen the shell of a former Walmart, it’s probably true.

Walmart stores sometimes have a surprisingly short lifespan. That includes immediately closing a store after workers unionized.

When Walmart leaves an area, the damage it generates for the local economy is only compounded.

Ten years. That’s all the time it took for the store to rise up in a clearing of the lush forest of West Virginia’s coal country and then disappear again, as though it had never been there. …

"It was a big thing for people round here when Walmart pulled out. People didn’t know what to do. Young people started leaving because there’s nothing for them here. It’s like we’re existing, but not existing.”

Costco isn't immune to closing stores. Since its founding, the retailer has closed 58 locations. However, it appears that all of these were done to replace early stores and stores opened during an early-90s flirtation with smaller Costcos (where "small" means only around 90,000 square feet) with newer sites that fit the current warehouse model. In fact, over half of all closures were near the company's home in Washington state, where they were usually replaced by another location within a mile or two of the original store. Some Costco locations have also been converted from general retail operations into a "Costco Business Center."

There may be instances in which Costco has permanently closed a warehouse without opening another in the area. I didn't find one. On both their employees and their site locations, Costco devotes more time and resources to making good choices. Then it sticks with them.

None of this is required

Neither Walmart nor Costco represents the extreme of what's possible within the system, but their choices showcase the contrasts within the bounds of American capitalism.

The most remarkable aspect of this story is what's in the first paragraph: This isn't a tale of a ruthless empire versus a warm and fuzzy commune. These are both large companies, generating substantial profits and navigating complex business arrangements to deliver favorable outcomes for their shareholders.

Nothing requires Costco to pay its employees well. Nothing requires Walmart to treat its employees like contestants in Squid Game.

These are strategies; two companies taking radically different approaches to the goal of putting money in the till. They are both operating within the boundaries of the system that we've created. There's no radical socialism here. The differences are not the result of government mandates or environmental regulations.

They just make different choices. No one makes them do it. They don't have to.

Remember that part about how the average Walmart supercenter has about 25% fewer employees than the average Costco Warehouse? Those fewer employees have to deal with 30 times as many items, more frequent restocking, and do it while getting less pay and fewer benefits. They work harder for less. By design. For stores that damage their local economy, and which are much more likely to simply pack up and leave. That's all a choice.

None of this makes the people running Costco into saints, though co-founder Jim Sinegal sure seems like a nice guy who remains dedicated to his company. Still, he's just a business guy operating on a theory that works for his stores and happens to boost surrounding communities.

It also doesn't make the people who run Walmart into monsters. They simply … Sorry. Scratch that. No matter how you look at it, they suck.

Comments

We want Uncharted Blue to be a welcoming and progressive space.

Before commenting, make sure you've read our Community Guidelines.