It’s been 170 years since Eunice Newton Foote showed that carbon dioxide traps the heat of the sun.

It’s been 130 years since Svante Arrhenius first calculated that rising carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere were capable of greatly warming the surface of the planet.

It’s been nearly 90 years since engineer Guy Stewart Callendar, using data from scattered measurements over the previous half-century, calculated that CO2 emissions had already warmed the Earth. This “Callendar Effect” was greeted skeptically by most scientists.

It’s been nearly 70 years since Charles D. Keeling started decades of regular measurements of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere atop the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawai’i.

It’s been nearly 50 years since Exxon scientists told their bosses that continuing to extract and burn fossil fuels would perilously heat up the climate.

It’s been nearly 40 years since climatologist James Hansen gave seminal testimony to Congress about the threat of climate change if humankind kept up its prodigious emission of greenhouse gases.

It’s been 36 years since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its First Assessment Report, laying the groundwork for international climate policy.

It’s been one year since Donald Trump yanked the United States out of the Paris Agreement again.

In all the years since its sixth assessment, the IPCC has produced five more, pouring out climate facts in abundance. Whatever flaws these and the gigatons of other climate studies contain, there’s an unambiguous message. The climate is rapidly changing. Human behavior is the key factor in making this happen. The changes are already creating great harm to countless species, altering ecosystems in ways not reversible on human timescales. Stopping these changes from getting worse requires stopping greenhouse emissions by stopping the burning of fossil fuels.

But many people just don’t buy it. Or they do but aren’t willing to support adequate action to address the peril. I’m not talking about the malefactors of the Trump regime and fossil fuel interests. Ignore their science denial. With the exception of the boss himself, they know the facts and scheme to navigate around them for the sake of their bottom lines. I’m talking instead about a very large cohort of rank-and-file Americans.

Facts have not failed to convince these people because the science is weak. It’s failed because human belief systems are not built to update like spreadsheets. Cognitive research shows that beliefs are deeply networked with other ideas and identities, so contradictory information often triggers defense, not revision. People are more willing to embrace new information they regard as positive news and ignore what they see as negative news, reinforcing what they already think. Even when people encounter evidence that clearly challenges a belief, they may generate new explanations to keep both the belief and the evidence “in play,” rather than abandon their original view.

This dynamic becomes far more pronounced when facts touch politics. Studies in psychology and neuroscience show that confronting evidence that threatens one’s worldview feels like a personal attack, activating emotional and cognitive defenses that block analytical reassessment. Rather than prompting calculation, contradictory facts can trigger what psychologists call belief perseverance and even a “backfire effect,” where the original belief strengthens in response to challenge. Meanwhile confirmation bias — the instinct to seek out data that confirms pre-existing beliefs — means that even highly educated audiences can interpret identical evidence in starkly different ways.

So when climate scientists and communicators point to the latest data on ocean heat, temperature thresholds, or greenhouse-gas forcing, they are entering a cognitive and cultural battleground where trust, identity, and power shape how information is perceived. Facts do not land in a neutral space but in a social ecology where media ecosystems, political interests, and group affiliation determine which facts count and which are dismissed.

This is why the empirical weight of reports with their tallies of record ocean heat, changing seasons, dangerously elevated temperatures, and spoiling of ecosystems mostly convincing those already inclined to listen. It’s why understanding the politics of persuasion is inseparable from confronting the climate crisis itself.

Consider, for instance, how climate facts are routinely filtered through political meaning. Rising ocean heat is framed by industry groups and allied politicians as a threat to “energy independence” or working-class jobs, recoding warning signs as attacks on livelihoods. Temperature thresholds, expressed through multilateral agreements and technical assessments, are dismissed by some conservatives as out-of-touch abstractions imposed by distant elites. And when climate action is framed as consumer choice or individual virtue, the structural drivers of emissions quietly disappear, absolving fossil fuel producers and governments of responsibility.

In each case, persuasion fails not because the science is unclear, but because political actors actively shape the interpretive frame through which that science is perceived, turning measurements into symbols of cultural conflict.

A key element is how climate facts (or any facts) get told. While they can be grim, horrifying, they typically are told in an aggregate, global fashion, instead of a local, personal way. This weakens their impact. As emptywheel (Marcy Wheeler) points out at her website in The Storytelling We Need to Rebuild Belief in Government:

Consider this WaPo story, “The year Trump broke the federal government.”

It tells the stories of hundreds of Federal workers, including those who left and those who stayed through the DOGE and Russ Vought massacres. It is great! But it also only mirrors the full story (and potentially buried in a holiday weekend).

It very poignantly captures the cruelty of Trump’s firings, such as this anecdote about a woman killing herself just after Elon Musk’s Five Things emails started.In Virginia, the family of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services worker Caitlin Cross-Barnet checked her into a mental health facility. She was struggling with despair after a difficult hysterectomy, and because she felt Trump was unraveling the government. In daily calls to her husband, she asked about changes to the federal workforce. Six days after the “What did you do” email, she killed herself.

While it describes many benefits shuttered, it doesn’t describe what happened to the people affected by these losses.

What happened, for example, when those working a suicide prevention line could no longer offer their clients privacy?

The State of the Climate 2025 analysis just released from Carbon Brief is filled with facts. By every major metric, it announces a climate transition well underway. It documents that the three hottest years in the instrumental record, with global mean temperatures clustered in the 1.3°C–1.5°C [2.34°F-2.7°F] above the pre-industrial range, depending on dataset and methodology. Over land, anomalies routinely approach or exceed 2°C [3.6°F]. The oceans, meanwhile, absorbed more heat in 2025 than in any year previously measured, pushing global ocean heat content to yet another record high — not a spike, but a continuation of a relentless upward trend.

Some highlights from the report:

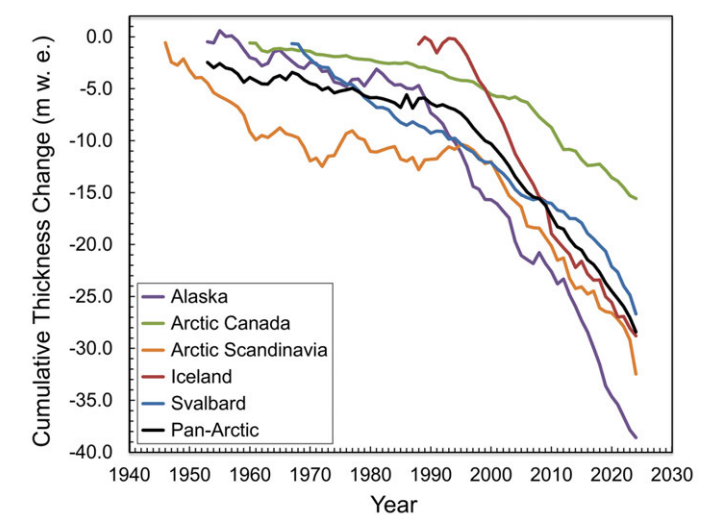

Ocean heat content: It was the warmest year on record for ocean heat content and one of the largest year-over-year increases in ocean heat content. In 2025, the oceans added 39 times more heat than all annual human energy use.Global surface temperatures: The year 2025 is effectively tied with 2023 as the second-warmest year on record – coming in at between 1.33C and 1.53C above pre-industrial levels across different temperature datasets and 1.44C in the synthesis of all groups.Second warmest over land: Global temperatures over the world’s land regions – where humans live and primarily experience climate impacts – were 2C above pre-industrial levels, just below the record set in 2024.Third warmest over oceans: Global sea surface temperatures were 1C above pre-industrial levels, dropping from 2024 record levels due to fading El Niño conditions.Regional warming: It was the warmest year on record in areas where, collectively, more than 9% of the global population lives.Unusual warmth: The exceptionally warm, record-setting temperatures over the past three years (2023-25) were driven by continued increases in human emissions of greenhouse gases, reductions in planet-cooling sulphur dioxide aerosols, variability related to a strong El Niño event and a strong peak in the 11-year solar cycle.Comparison with climate models: Observations for 2025 were nearly identical to the central estimate of climate model projections in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sixth assessment report (AR6).Heating of the atmosphere: It was the second warmest year in the lower troposphere – the lowest part of the atmosphere.Sea level rise: Sea levels reached record highs, continuing a notable acceleration over the past three decades.Shrinking glaciers and ice sheets: Cumulative ice loss from the world’s glaciers and from the Greenland ice sheet reached a new record high in 2025, contributing to sea level rise.Greenhouse gases: Concentrations reached record levels for carbon dioxide (CO2), methane and nitrous oxide.Sea ice extent: Arctic sea ice saw its lowest winter peak on record as well as its 10th-lowest summer minimum extent, while Antarctic sea ice saw its third-lowest minimum extent.Looking ahead to 2026: Carbon Brief predicts that global average surface temperatures in 2026 are likely to be between the second and fourth warmest on record, similar to 2023 and 2025, at around 1.4C above pre-industrial levels.

For climate scientists and non-scientists who have followed their data and its interpretations over the past decade, the meaning is unmistakable. We’re no longer observing early-stage warming dynamics. We are watching a mature, anthropogenically driven energy imbalance express itself across multiple Earth systems simultaneously.

In its State of the Climate 2017, the Carbon Brief team emphasized that ocean heat content had reached record highs even in the absence of strong, heat-boosting El Niño conditions, underscoring that the system’s momentum was being driven by cumulative greenhouse-gas forcing rather than short-term variability.

The 2025 data make clear the oceans no longer buffer warming so much as redistribute it. Elevated sea surface temperatures intensify tropical cyclones, increase atmospheric moisture loading, and accelerate thermal expansion, locking in sea level rise irrespective of near-term emissions trajectories.

The impacts intensified by record ocean heat — coastal flooding, extreme rainfall, storm surge, and fisheries collapse — disproportionately affect populations with the least political leverage and the fewest resources to adapt. The climate system may be indifferent to borders, but political economy is not. Wealthy states and corporations retain insulation through infrastructure, insurance, and mobility, while frontline communities absorb compounding shocks.

A clear-eyed reading of the State of the Climate 2025 demands a break with the assumption that existing economic arrangements can be gently nudged into alignment with planetary limits. They cannot. But how does this help us convince people not yet persuaded? The report contains countless possibilities for crafting local, personal stories. The kind that make facts persuasive for audiences that will never read a climate report. Yes, there are such stories, but not nearly enough for what should be a media stream at least as relentless as its celebrity and crime streams.

See also:

The 2025 state of the climate report: a planet on the brink (American Institute of Biological Sciences)

The Global Risks Report 2026 (World Resources Forum)

Comments

We want Uncharted Blue to be a welcoming and progressive space.

Before commenting, make sure you've read our Community Guidelines.